Frailty is a common concern for patients with advanced heart disease. Most people understand what we mean when we refer to someone as frail. In medicine, frailty can be defined as a loss of fitness and reserve. While often associated with aging, frailty accompanies many forms of heart disease, even in those who are younger.

Heart disease treatments have advanced tremendously and some, such as mechanical assist devices and heart valve implants, can be especially beneficial to even advanced conditions, as long as patients have the physical reserves to recover from an invasive procedure. “A challenge in clinical medicine is identifying what we refer to as ‘reversible frailty,’ that is the loss of conditioning and physical reserve that is the result of the heart disease itself, and which is predicted to reverse with treatment,” said Nancy K. Sweitzer, MD, PhD, a cardiologist who specializes in advanced heart failure and heart transplant.

To improve patient frailty assessments and identify cases in which frailty is likely to be reversed with treatment, Dr. Sweitzer is collaborating with Nima Toosizadeh, PhD, a biomedical engineer who has been studying frailty with the University of Arizona Center on Aging. They are conducting a clinical research study to develop a reliable frailty score and use it to set parameters to predict patients most likely to benefit from an invasive cardiovascular procedure versus someone whose frailty is not solely due to the heart condition, and who is therefore less likely to recover and improve following a procedure.

“I love partnering with patients, listening to their goals and concerns, and developing treatment plans that help them reach their goals. Currently, measurements for conditions such as frailty are imprecise and do not help us detect the reversible component in a frail patient. The technology we are using in this study shows potential for removing some of this uncertainty and may give clinicians a tool to accurately measure frailty, reversible frailty and provide better data for guiding a patient through the decision-making process,” said Dr. Sweitzer, who is director of the Sarver Heart Center and professor of medicine at the UArizona College of Medicine – Tucson.

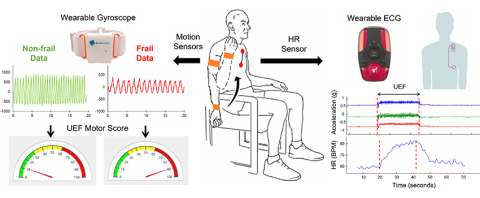

Dr. Toosizadeh’s research model includes sensor patches that measure heart-rate changes in response to a physical task involving the arm, which can be done even when the patient is in bed. Heart rate is measured at rest, during 20 seconds of fast elbow flexion, and then tracked during recovery.

“This model has been used to assess frailty in other conditions such as in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and those going through elective surgery. Findings show a strong association between our frailty score and longitudinal outcomes including hospital complications and risk of readmission. This new research will enable us to develop a heart rate risk score, specifically for heart failure and aortic stenosis. Both are common conditions of aging and may respond very well to aggressive surgical intervention,” said Dr. Toosizadeh, assistant professor of medicine and biomedical engineering, and part of the UArizona Center on Aging.

This is one example of the more than 20 clinical research studies underway in Sarver Heart Center’s Cardiovascular Clinical Research Program. To learn more about clinical research at Sarver Heart Center, visit SARVER HEART CENTER CLINICAL RESEARCH